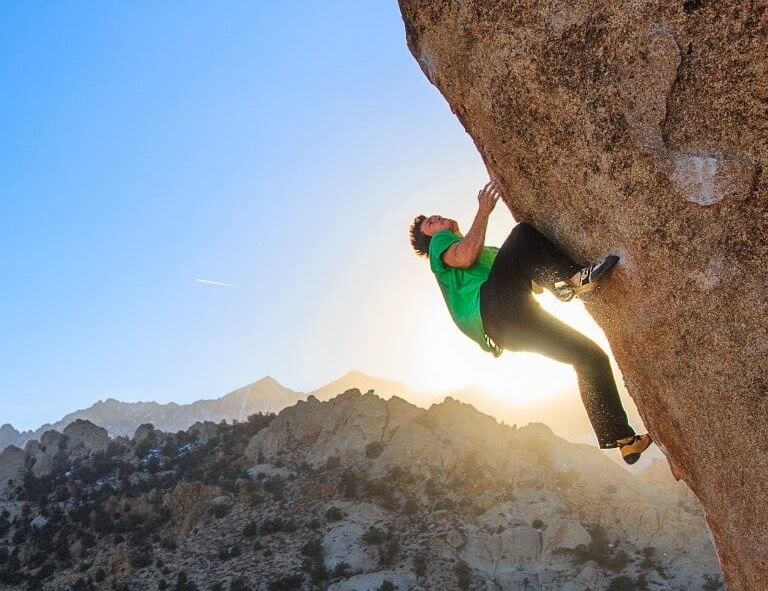

Bouldering Amongst the Buttermilk Rocks of Bishop California

September 6, 2018 | Doug Robinson

Photo Credit | Doug Robinson

Whether on a pilgrimage of sorts, or simply searching for a physical challenge, climbers flock to discover the birthplace of bouldering. Bishop, California, is known as a bouldering mecca, where you can find 30 to 80 cars parked out Buttermilk Road at the Peabodies and the Birthday Boulders. With more climbers arriving almost daily to step out of their vans into sand and sage, it’s difficult to realise that all this began 76 years ago, when an unassuming Buddhist truck driver wandered into a now nearly forgotten part of the Buttermilk.

Climbing without climbing gear

Bouldering has skyrocketed in popularity, often thanks to its easier access and lower danger levels. ‘Pebble wrestling’ is one of its catchier descriptions. It’s a passion for small climbs that have become almost ridiculously difficult.

Boulderers climb without climbing harness or gear, but make liberal use of foam pads to break the frequent falls taken while working out intricate sequences of moves. It’s challenging physically and mentally, and offers endless hours of fun in the great outdoors.

Bouldering emerges in California

Why did the Buttermilk become ground zero for bouldering? Few know the story of how climbing there owes its inspiration to a self-effacing guy in a flat hat and leather hiking boots.

Enter Smoke Blanchard, who became Bishop’s first rock climber in 1941. Smoke grew up in Portland, where he made first ascents, speed climbs and ski descents on Mt. Hood before moving to California to drive a propane truck (yes, diesel smoke gave him his name), a winter job that left his summers free for climbing. Smoke bumped along Buttermilk Road and wandered into the maze of rocks. But it wasn’t the boulders he was drawn to at first.

Instead, Smoke liked the bedrock granite just downslope from the famous boulders. The confusion of box canyons, chimneys, rounded gargoyles and even tunnels is about half a mile wide and runs up the hillside for nearly a mile. Compared to the boulders, almost no one ventures into Smoke’s rocks now.

Smoke Blanchard Invents Bishop Bouldering

Consequently, very few have heard of Smoke’s Rock Course, his creation that winds its way through the maze, opening a line of possibility that visits a dozen small summits along the way. Fewer still have experienced its gritty delights, the utterly unique style of climbing Smoke forged there, mostly all alone on the curdled-buttermilk looking formations.

Smoke called it “mild mountaineering,” and while move-by-move the climbing is easier than bouldering, it’s a different beast, uniquely its own form of ascending, and there’s little comparison between the two.

Strange as Smoke’s not-really-so-mild mountaineering seems to modern sensibilities – attuned as we are to the luxury of nylon ropes and climbing shoes – it’s heir to a venerable tradition. No question that rock climbing is remarkable, and that it inspires us to push our own limits, but it also has inadvertently dulled our sensibilities to older modes of being on rock. Like the continuously free-flowing movement over easier - though not truly “easy” - climbing.

The ‘Flow’ of Bouldering

There’s a sweet spot on the difficulty scale. Let’s call it 5.4 to 5.7, but it’s a personal scale in truth. You get to go figure your own. Come to think of it, Smoke’s Rock Course throws in liberal doses of fourth class terrain. Even third. You know it by the flow. It’s where you move over the rock as a dancer, before compounding difficulty makes you slow down and sweat and know fear of flying. It partakes of a sheer joy in moving, in the movement itself. High enough off the deck to matter, it takes all the humility of full attention, yet it’s (mostly) short of being consumed by the fright of falling off. Flow is a good word for it. For the way you can keep moving gracefully. And of course for the head space that flows right out of that movement.

John Gill, who pretty much invented bouldering, called it “…a remarkable feeling of lightness and detachment”.

The Rock Course is a full-body workout. Following Smoke you’ll feel the skyline change with your effort. Even in one of his trademark chimneys, squirming up a narrow slot where you break a sweat to gain purchase through the effort, move by move, of pushing the walls apart, suddenly you’re several stories higher.

Smoke put it well in his book, Walking Up and Down in the World: Memories of a Mountain Rambler. “There is no way that I know of to pass on by paper,” he wrote, “the feeling that permeates the person who steps out of the shower with epidermis cleaned and tingling from crystal scrapes, muscles pleasantly tired, joints well-oiled, and mind and spirit glowing from a full day of Buttermilking.”

Picnic and Pilgrimage

Actually, a “full day” is asking a lot. The last time I went on the Rock Course, with a dozen new aspirants, we managed to get over three out of its dozen summits. That took a leisurely half day, pausing as we did to chat, tell Smoke stories, and admire many views. Then of course there was the stop in Picnic Valley, with a tablecloth of snacks spread on the sand, part of a tradition Smoke called a “combination of picnic and pilgrimage.”

As the cheese and crackers got packed away and last sips of wine were savoured, three leaders were already on their way up parallel chimney lines on Big Slab Pinnacle. They trailed 50-foot chunks of skinny rope (Smoke called it his “string”), the only piece of climbing gear we carried. We revived simple mountaineering practices of the past, with old-school bowline-on-a-coil tie-ins for followers, while belaying without hardware by simply being seated securely in a hollow in the rock, just to stop a slip.

Chasing Challenging Peaks

Older climbers knew a joy in robust movement that we moderns, chasing mere difficulty, have sometimes forgotten. Classical mountaineers, struggling to summit ever more challenging peaks, kept pushing the difficulty of climbing right on up into fully fifth class moves. Legendary then, long before the rope was introduced to climbing, their exploits are now largely overlooked.

Take Paul Pruess. A hundred years ago his bold solos defined what was possible. A video of a modern repeat of one of his routes, climbing a thousand-foot tower of limestone in Italy’s Dolomites, conveys the quality of his climbing.

How About Some Bishop Bouldering?

Or we could look back to ancient China. The poetry in Smoke’s library led me to Han Shan, a seventh-century “mountain madman” whose exploits among the misty towers that practically define Chinese scrolls helped give birth to Zen. An elusive character, he lived in caves among the cliffs of Cold Mountain and left his poems scrawled on the cliffs. He wrote,

The path to Han-Shan’s place is laughable,

Converging gorges - hard to trace their twists

Jumbled cliffs – unbelievably rugged

In the greater scheme of things, of course, climbing is laughable. But then we are primates; it’s in our blood.

This venerable tradition is the wellspring of Smoke’s mild mountaineering, of the grand climbing lineage he’s carried onto his Rock Course. Too bold to be silly, too admirably stout to be dismissed as scrambling. But the proof is in the climbing. I’d call it noble, even, though in truth, its sheer sweaty reality has a groveling quality that keeps it refreshingly honest. Smoke’s Rock Course, after all, reminds us of being in the world with full immediacy. How about it?

More for you

What is a bouldering gym | icebreaker

25 October 2017 | The Field

Hiking Adventure in the Gobi Desert | icebreaker

August 30, 2019 | Laura Charabot

Antarctica, the place of extremes | icebreaker

25th March, 2017 | Damian Christie